If you’ve ever watched a football game and wondered how quarterbacks and receivers seem to communicate so perfectly, the answer lies in something called the football route tree. This simple numbering system is the secret language of the passing game, and learning it can transform how you watch, play, or coach the game.

What Is the Football Route Tree? (Football 101)

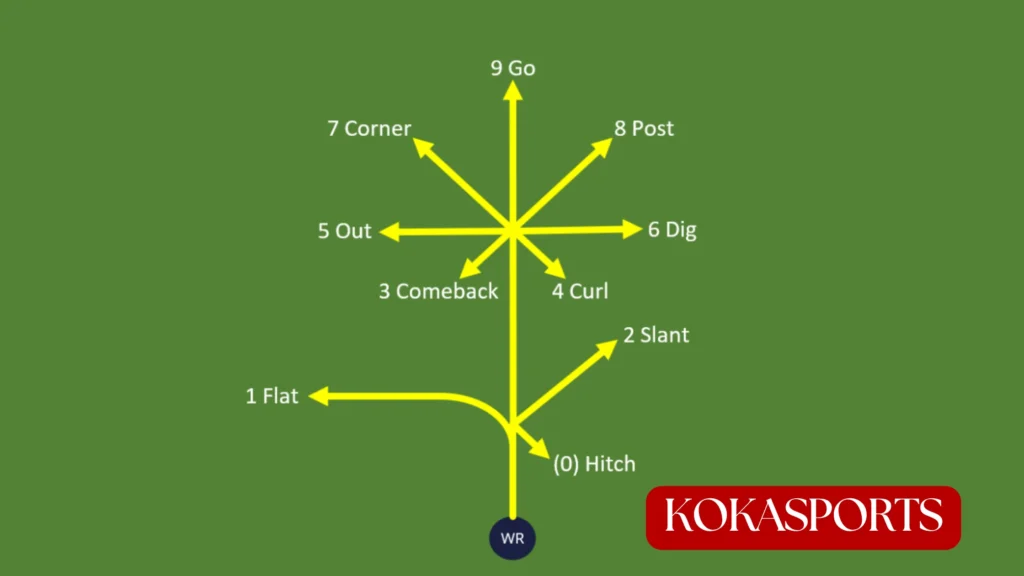

The route tree is a numbered system that assigns specific routes to numbers 1 through 9. Think of it like a menu at a restaurant each number represents a different dish, or in this case, a different path the receiver will run on the field. When a quarterback calls a play, receivers know exactly where to go based on these numbers.

The beauty of this system is its simplicity. Instead of saying “run 15 yards straight, then cut hard to your left toward the middle of the field,” a coach or quarterback can simply say “run a 6.” Every receiver in organized football learns this tree, from youth leagues all the way up to the NFL.

The route tree starts at the line of scrimmage and branches out like an actual tree. Routes numbered 1-3 are typically shorter, quick-hitting routes. Routes 4-6 are intermediate routes that break between 10-15 yards. Routes 7-9 are your deeper routes that attack downfield. This organization helps offensive coordinators design plays that attack different levels of the defense simultaneously.

Read More: Twins Formation Football: Complete Guide to Strategy, Plays, and Playbook Design

The 9 Routes Explained: Route by Route Breakdown

Route 1 – The Flat Route

The flat route is the shortest route in the tree, usually run about 1-5 yards downfield before breaking toward the sideline. This quick-hitting route is perfect for getting the ball out fast against aggressive defenses. The receiver sprints hard off the line of scrimmage, then breaks sharply toward the sideline, staying parallel to it.

This route is often run by running backs, tight ends, or slot receivers who need to get open quickly. Against zone coverage, the flat route exploits the space between linebackers and defensive backs. The quarterback usually makes this throw within two seconds of the snap, making it a safe, high-percentage option when the offense needs a quick gain or wants to attack the edges of the defense.

Key coaching point: The receiver must get his head around quickly after the break. The ball arrives fast, and hesitation means an incomplete pass or worse a defender making a big hit.

Route 2 – The Slant Route

The slant is one of the most fundamental football routes you’ll see at every level. The receiver takes 2-3 hard steps upfield, then plants and cuts at a 45-degree angle toward the middle of the field. Timing between the quarterback and the receiver is critical here the ball should be leaving the quarterback’s hand as the receiver makes his break.

Slant routes are excellent against man coverage, especially when the defender is playing with outside leverage. The route creates natural separation as the receiver cuts inside, and if the defender isn’t looking for it, the slant route can turn into a huge gain. Many NFL teams use slants as their primary quick passing route because it’s effective and relatively safe from interceptions.

The outside receiver typically runs this route most effectively, though inside receivers can run slants too. The receiver breaks toward the quarterback’s throwing shoulder, making it easier to complete even under pressure. This route is also common in RPO (run-pass option) plays where the quarterback reads the defense and decides whether to hand off or throw the slant.

Route 3 – The Comeback Route

The comeback route requires patience and excellent footwork. The receiver runs straight upfield for 12-15 yards, selling the defender on a deep route, then suddenly stops and comes back toward the line of scrimmage a few steps. This route is effective against both man and zone coverage when executed properly.

The comeback works best when the receiver creates vertical separation first. If a defensive back is playing soft coverage (giving cushion), the comeback route allows the receiver to settle in the open space. The receiver must have strong hands and body control because the throw often arrives while he’s coming back toward the quarterback, and defenders can close quickly.

This route is particularly useful along the sideline, where the receiver can use the boundary as an extra defender. The quarterback needs to throw with anticipation, putting the ball on the receiver’s outside shoulder to protect against interceptions. At the NFL level, veteran receivers master this route because it requires reading the defender’s positioning and adjusting the depth accordingly.

Route 4 – The Curl Route (Hook Route)

The curl route is similar to the comeback but breaks at a slightly different depth and direction. The receiver runs 8-12 yards upfield, then curls back toward the quarterback while facing the line of scrimmage. This route is one of the most reliable passing routes for moving the chains on third down.

What makes the curl effective is how the receiver positions his body at the top of the route. By curling inward rather than coming straight back, the receiver creates a natural throwing window for the quarterback. Against zone coverage, the curl route finds soft spots between defenders. Against man coverage, the receiver’s sudden change of direction creates separation.

Slot receivers and inside receivers often excel at this route because they have more field to work with when breaking toward the middle of the field. The route breaks around 10 yards typically, making it an intermediate route that balances safety with explosive potential. If the receiver catches the ball cleanly with space ahead, he can generate significant yards after the catch.

Route 5 – The Out Route

The out route requires precision and proper technique. The receiver runs 10-12 yards upfield, then plants hard on his inside foot and cuts at a 90-degree angle toward the sideline. This route attacks the width of the field and tests the receiver’s ability to create separation with sharp cuts.

Timing is everything on out routes. The quarterback must throw before the receiver completes his break, trusting that the receiver will be in the right spot. If thrown late, defenders can jump the route for interceptions. The outside receiver runs this route most frequently, though it can be effective from any receiver position.

Against press man coverage, receivers need to sell vertical movement before breaking outside. Against zone, the out route finds windows between defenders dropping into their assigned areas. To run an out route successfully, receivers must snap their hips quickly and accelerate out of the break toward the sideline. The route is effective because it gets the ball outside quickly while keeping it away from middle defenders.

Route 6 – The Dig Route (In Route)

The dig route is the mirror opposite of the out route. The receiver runs 10-15 yards downfield, then breaks sharply toward the middle of the field at a 90-degree angle. This crossing route is excellent for attacking zone defenses and finding holes in coverage.

What makes the dig dangerous is the space it creates across the field. The receiver runs straight upfield first, forcing defenders to respect the vertical threat, then breaks inside where linebackers have often vacated for run support or deeper zone drops. The dig route requires courage because receivers are running into traffic, but it also creates opportunities for big plays.

The route is often run by the outside receiver who has the most field to cross. Against Cover 2 or Cover 3 zones, the dig finds the seam between defensive backs and linebackers. The quarterback needs to throw with velocity on this route soft passes get picked off by alert defenders. When executed well, the dig becomes a great route for moving the ball methodically down the field.

Route 7 – The Corner Route

The corner route attacks the deep outside portion of the field, specifically targeting the corner of the end zone in scoring situations. The receiver runs 12-15 yards upfield, then breaks at a 45-degree angle toward the sideline flag. This route is particularly effective against Cover 2 zone defense, which has a natural hole between the cornerback and safety.

Running this route requires the receiver to sell a post route initially, making the defender think the ball is going to the middle of the field. Then, the receiver suddenly breaks back toward the sideline. The deception creates separation and forces defenders to make difficult recovery moves. The corner route is also excellent in the red zone because it uses the limited field space efficiently.

NFL receivers spend countless hours perfecting the subtle head fakes and body language that make the corner route successful. The route is used frequently in play-action passes where the fake run holds safeties, creating more space on the outside. When the receiver executes properly, this route produces touchdowns and big chunk plays down the field.

Route 8 – The Post Route

The post route is one of the most iconic routes in football. The receiver sprints 12-15 yards downfield, then cuts at a 45-degree angle toward the middle of the field, aiming for the goal posts (hence the name). This deep route requires speed, precise angle work, and excellent ball tracking skills.

What makes the post route special is its explosive potential. When defenders bite on the vertical release or play too far outside, the post creates a clear path down the middle. The quarterback needs a strong arm to deliver the ball accurately at this depth, and the receiver must adjust his speed to stay in sync with the throw.

The post route works best against single-high safety looks where the middle safety has to choose which receiver to cover. It’s also effective against defensive backs playing with inside leverage the receiver can use his speed to run past them toward the middle. At the NFL level, timing on post routes is crucial. The ball often travels 40-50 yards in the air, requiring perfect coordination between passer and receiver.

Route 9 – The Go Route (Fly Route, Streak Route)

The go route is the simplest yet most dangerous route in the tree. The receiver runs straight down the field as fast as possible, trying to run past the defender for a deep completion. This vertical route is also called a fly route, fade route, or streak route depending on the region and offense.

Despite its simplicity, the go route requires excellent technique. The receiver must get off the line of scrimmage cleanly against press coverage, maintain a straight line, and track the ball over his shoulder. Against soft coverage, the receiver can build up speed gradually. Against press coverage, the receiver needs quick hands to defeat the jam and acceleration to separate vertically.

The go route is often used to stretch the defense vertically, creating space underneath for other routes. It’s also the ultimate shot-play route when everything connects, it results in touchdowns. Receivers who excel at this route typically have a combination of speed, ball tracking ability, and body control to adjust to throws. The route is usually run by outside receivers with elite speed who can threaten defenders deep.

How Routes Work Together: Route Combinations

Individual routes become deadly when combined strategically. Route combinations create conflict for defenders by putting them in impossible situations. For example, a common concept pairs a flat route (#1) with a corner route (#7). This “flood” concept forces the cornerback to choose between defending the short flat or the deep corner he can’t cover both.

Another popular combination is the slant-flat, where an inside receiver runs a slant (#2) while an outside receiver runs a flat route (#1). This combination attacks different levels simultaneously and creates easy reads for quarterbacks. The dig-post combination forces middle defenders to choose between two receivers crossing their zone at different depths.

These concepts show why learning the route tree matters. When coaches design plays, they’re thinking about how different routes force defenders into conflicts. The numbering system makes it easy to call these combinations instead of explaining each player’s assignment in detail, a coach can simply say “we’re running 276” and everyone knows exactly what route to run.

Route Tree Variations Across Football Levels

| Level | Route Depths | Common Routes | Key Differences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Youth Football | 3-8 yards | Slant, flat, go | Simplified tree, shorter depths |

| High School | 5-12 yards | Full tree with less complexity | Standard depths, basic concepts |

| College | 8-15 yards | Full tree, option routes | More sophisticated timing |

| NFL | 10-20 yards | Full tree, sight adjustments | Precise depths, complex concepts |

The basic routes remain consistent across levels, but how they’re executed changes dramatically. Youth players might run a short route at 5 yards that NFL receivers run at 12 yards. The route is typically shorter for younger players because they lack the arm strength and timing precision of older athletes.

Teaching the Route Tree Effectively

Coaches should introduce the route tree systematically, starting with the most fundamental routes. Begin with routes 1, 2, and 9 the flat route, slant, and go route. These three routes form the foundation because they’re simple and address different areas of the field. Once players master these basic routes, add the curl and out routes (4 and 5).

Practice should emphasize the relationship between each route and defensive coverage. The receiver needs to recognize when a route is effective based on how defenders align. For instance, the slant works best against outside leverage, while the comeback works against soft coverage. Teaching this concept helps receivers adjust when the route may need slight modifications based on the defender’s position.

Footwork drills are essential. The quality of a receiver’s route depends on how cleanly he can change direction at the break point. Setting up cones at the appropriate depths helps receivers develop muscle memory for when the route breaks occur. The receiver makes subtle adjustments based on game speed, but practice reps build the foundation.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Many receivers struggle with route depth consistency. Running a route at 8 yards when it should be at 12 yards throws off the entire timing with the quarterback. The route where the receiver breaks must be precise, or the play collapses. Coaches should use markers during practice to reinforce proper depths.

Another common error is failing to accelerate out of breaks. The receiver should explode out of cuts, not drift. The fastest part of running this route should be after the break, when the receiver to get separation matters most. Lazy footwork telegraphs routes to defenders and reduces effectiveness.

Reading coverage incorrectly causes many route failures. An option route requires the receiver to choose between two directions based on the defender’s leverage. If the receiver makes the wrong read, the quarterback’s throw goes to empty space. Teaching coverage recognition should happen alongside route technique they’re inseparable skills.

Why the Route Tree Matters for Everyone

For quarterbacks, the route tree provides a mental framework for reading defenses. Knowing where receivers should be at each point allows quarterbacks to throw with anticipation rather than waiting to see receivers open. This split-second advantage makes the difference between completions and sacks.

For receivers, mastering routes in the tree separates good players from great ones. The wide receiver position demands precision because even slight deviations from the route affect the entire play. Professional scouts evaluate how cleanly receiver routes are executed because it indicates football intelligence and discipline.

For coaches, the route tree is the universal language of offensive design. Whether installing a spread offense or a pro-style attack, the numbered system allows quick, efficient communication. Play-calling becomes simpler when everyone speaks the same language, from the tight end to the wide receiver.

Even fans benefit from knowing the route tree. Watching games becomes more engaging when you can anticipate which route each receiver can run based on the formation and defensive alignment. You’ll notice why certain passing routes work against specific coverages and appreciate the chess match happening pre-snap.

Conclusion:

The football route tree transforms the complex passing game into a simple, elegant system. Those nine routes from the quick flat route to the explosive go route form the building blocks of every passing offense in modern football. Whether you’re a player, coach, or fan, mastering these routes gives you the foundation to succeed.

The receiver who perfects these routes becomes invaluable. The quarterback who knows them instinctively can dissect any defense. Take time to study each route, watch how NFL receivers execute them, and you’ll see the game in an entirely new way. The route tree isn’t just a diagram it’s the language that allows the receiver and quarterback to achieve perfect synchronization on the field.

FAQs

Which is a 7 route in football?

The 7 route is the corner route, where the receiver runs 12-15 yards upfield then breaks at a 45-degree angle toward the sideline.

What is a route tree in football?

A route tree is a numbered system (1-9) that assigns specific passing routes to each number, helping quarterbacks and receivers communicate efficiently.

What is a five route in football?

The 5 route is the out route, where the receiver runs 10-12 yards upfield then cuts at a 90-degree angle toward the sideline.

What is the levels route in football?

The levels route is a passing concept where multiple receivers run routes at different depths (short, intermediate, deep) to create a high-low read for the quarterback.